No proven treatment: The dilemmas doctors face on the COVID-19 frontline

Devex

Jenny Lei Ravelo and Amruta Byatnal

July 8, 2020

MANILA/NEW DELHI — In late June, a 21-year-old man who tested positive for COVID-19 visited the Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences accompanied by his parents. The hospital is located in Sevagram in the western part of India, and caters to a mostly rural population.

“Whatever is available in the world, we can get it,” the worried parents told Dr. SP Kalantri, director professor of medicine at the hospital.

This is part of our Duty of Care series

This series explores how health systems can better support and protect health care workers.

It was the week that the Indian government had issued a clearance for the anti-viral drug favipiravir for restricted emergency use to treat mild-to-moderate COVID-19 patients, and Kalantri had already been asked about its efficacy by patients. However, he was skeptical, given the high costs and low evidence for the drug.

“They had no idea how much the drugs would cost, but they were desperate,” Kalantri told Devex.

Instead of prescribing drugs that were still under investigation, Kalantri chose to counsel the parents of the 21-year-old.

“He was a healthy person without any other health conditions such as cancer or diabetes. So there’s a 99 % chance that he would come out of this relatively fine. And there was no need for expensive drugs,” he said.

As coronavirus cases reach over 10 million this week, with the death toll of over half a million people, and no drug found to be effective, doctors on the frontline around the world are making hard choices — whether to resort to standard care management or subscribe to strict protocols in administering investigational therapies, while carefully weighing the benefits and risks of these drugs.

Lack of evidence

Amid contentions over the beneficial effects of hydroxychloroquine, the Brazilian government continues to recommend it to treat COVID-19. But the guideline is not unanimously followed by doctors across the country.

Dr. Christiane Cimini, a specialist in intensive care medicine at a hospital in Teófilo Otoni, told Devex they are not providing these drugs to COVID-19-positive patients. Instead, they manage patients’ symptoms, such as through the use of mechanical ventilation and hemodynamic support. Patients with a bacterial infection are given antibiotics.

“We don’t have enough evidence that the use of these drugs improve prognosis, that’s why we don’t use them,” she said.

Other investigational drugs meanwhile such as remdesivir and tocilizumab are “very expensive” and are not widely available in the country, she said.

“Remdesivir is not available in Brazil, and tocilizumab can be found only in big centers.

In small towns and poor regions like the one I live in, it is not available,” Cimini said.

The United States this week bought almost all of Gilead’s stocks of remdesivir for the next three months.

Doctors at the General Hospital of Vitória da Conquista in Bahia, Brazil, are also only providing medication to address symptoms of the disease, but not hydroxychloroquine as there is no sufficient evidence to date on its efficacy and safety for patients, said Márcio Galvão Oliveira, professor of clinical pharmacy at the Federal University of Bahia, who also trains clinical pharmacy residents at the hospital. He said a number of medical societies are also not recommending the use of chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 patients.

“In Brazil, it’s a crazy situation … And we can say that the country is divided. Some doctors prescribe it, but most of the doctors don’t … because there is no evidence,” he said, adding that this is confusing patients.

“The president says to the population: Use hydroxychloroquine … [It] kills the virus. And the physicians say: I won’t prescribe it because there is no evidence. And the population [doesn’t] know [whether they] will trust the president or … trust the health professionals,” Oliveira said.

The need for consent

In Brazil and other countries such as the Philippines, doctors emphasized the importance of consent.

At a tertiary health facility in Manila dedicated to treating COVID-19 patients, doctors have been careful in ensuring patients receiving the investigational drugs fit the criteria. That means, for example, that patients found to have cardiac or heart problems and in severe and critical conditions are not given hydroxychloroquine, said Dr. Hanz Saliendra, fellow-in-training infectious disease specialist at the facility.

Saliendra said he is aware of the inconsistent results coming out of different studies on hydroxychloroquine, including those that revealed the drug does not provide any clinical benefits, and at times, increases the mortality risk of patients. But he also noted that a lot of the studies were done outside of the Philippines.

“The effect of the drug differs for different people, so it doesn’t mean it won’t work here. But we’re very vigilant in giving hydroxychloroquine,” he said.

Today, hydroxychloroquine is no longer given to patients at the hospital, after the World Health Organization stopped that arm of its clinical trial. Patients who enroll in the trial are instead offered tocilizumab and remdesivir. Saliendra emphasized the importance of patient consent in receiving the drugs, even if in some cases patients refuse doctor recommendations.

“When we gave those medications, we’ve seen clinical improvement. So our dilemma is when we foresee that the patient will improve if this medication is given to them, but they refuse to sign, we can’t push through in giving the drug/s,” he said in a mix of Filipino and English.

It’s saddening, he said, as the medications are available and patients don’t have to pay for anything. But “you cannot force them to sign, even if you know as a doctor there can be a clinical benefit,” he said.

Some patients would immediately balk at the term “study drug,” and it can be hard to convince relatives when they learn that a drug is under trial, Saliendra said.

WHO says “it can be ethically appropriate” to offer patients experimental therapies outside clinical trials when no proven effective treatments exist; it is not possible to initiate clinical studies immediately; the patient or representative has given informed consent; or when emergency use of the intervention is monitored and results documented.

“The decision to offer a patient an unproven or experimental treatment is between the doctor and the patient but must comply with national law. Where it is possible and feasible for the treatment to be given as part of a clinical trial, this should be done unless the patient declines to participate in the trial,” according to the WHO interim guideline.

Dr. Monica Pia Reyes-Montecillo, an infectious disease specialist practicing in six big hospitals in Laguna, in southern Manila, wrote to Devex that even if the hospitals she works in are not part of any clinical trials on COVID-19, written consent is of the utmost importance when they offer investigational drugs, such as tocilizumab and lopinavir/ritonavir, to patients. It’s important also, she said, to tell patients that there’s no guarantee of treatment success for investigational drugs.

“We tell patients that recommendations change as evidence comes in. Previously, hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine were among the drugs used off-label for COVID, and they are the most accessible among all [treatment options]. However recent evidence [has shown] that [hydroxychloroquine has] no significant effect on its use for COVID patients,” she said.

Mental health concerns, and shortage of doctors

Ensuring they are providing the best available treatment to COVID-19 patients, however, is not the only dilemma medical professionals face at work. Some worry over the mental health toll the disease is having on hospitalized patients and their families. Hospitalization can last from a week to a month, and patients are often left alone without family in the hospital, as part of infection prevention and control measures.

“Most patients are worried about their health condition, but we must not forget that mental health should always be assessed as well. The support system given by the families and health care workers is something that patients would always cite as a factor that boosts their morale,” Reyes-Montecillo said.

Kalantri believes that patients need an explanation of the limitations of the treatments available, but he also thinks it is the doctors’ responsibility to reduce panic, which has been a common phenomenon in this pandemic. “We need to communicate well. We need to sit with them and explain. All they need is some kind of support. They want to hear from their doctors. When there is trust between the medical community and the public, it is challenging but not difficult,” he said.

In Brazil, there are concerns over shortages of sedatives, which is needed by COVID-19 patients on mechanical ventilator support.

Others, meanwhile, are concerned about people presenting to health facilities when their symptoms are already severe, as in the case in Hodeidah, Yemen, where Médecins Sans Frontières is helping train health workers and running two hospitals, the Al Salakhana and Ad Dahi.

Dr. Dagemlidet Worku, MSF medical lead in Hodeidah, thinks part of this is due to early rumors — that people who presented themselves at health facilities and were confirmed to have COVID-19 would be subject to “mercy killings” — that scared people away, although these rumors have since subsided.

The mortality rate is high for patients presenting to the health facilities, but with limited testing and a health system affected by years of conflict, it’s hard to know the real gravity of cases there, he said.

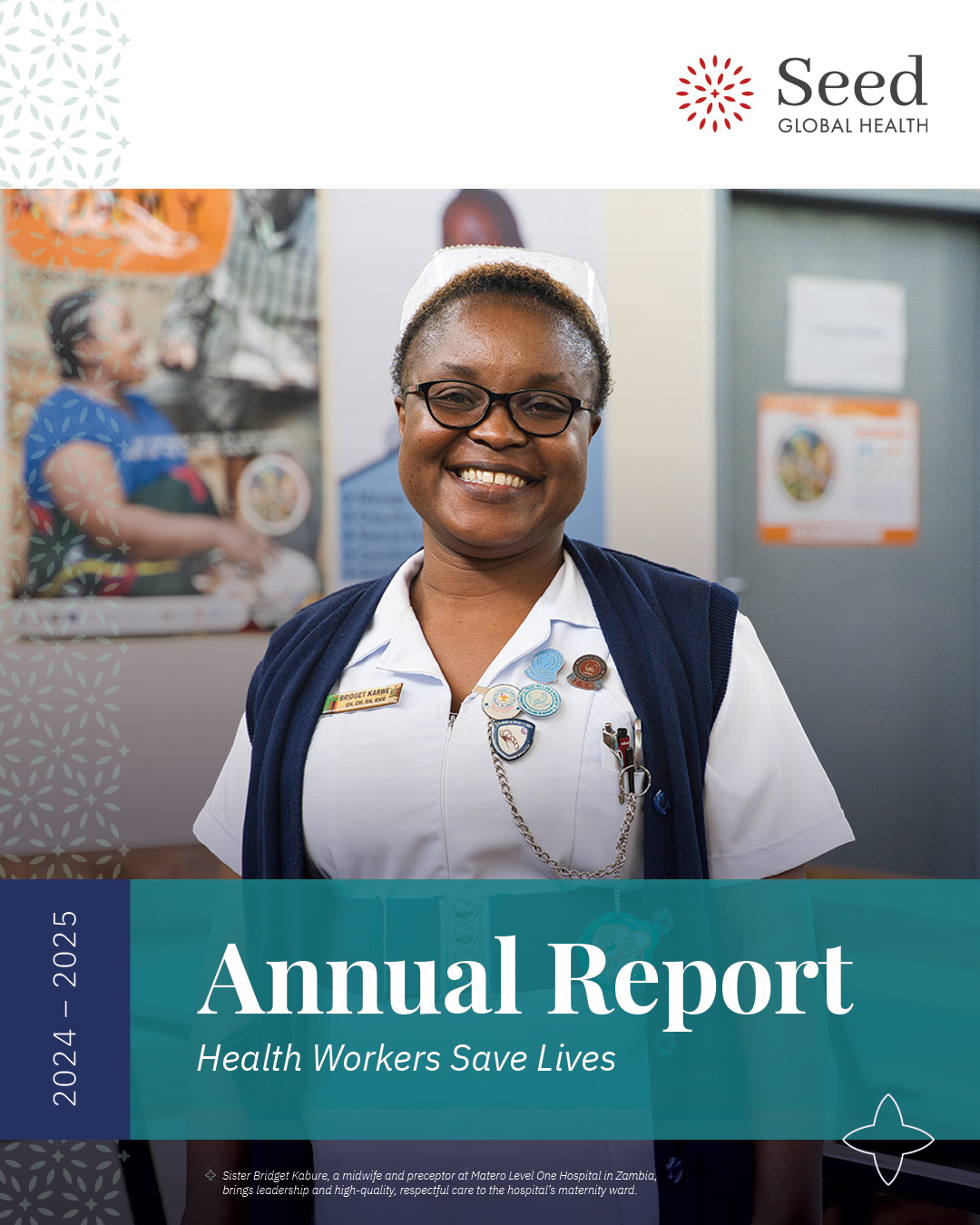

Others are concerned over the limited number of trained health professionals to handle a potential increase in cases. In Zambia, Dr. Bassim Birkland, teacher of family medicine at Chilenje Hospital in Lusaka and Zambia country representative for Seed Global Health, said that while more personal protective equipment is coming into the country, and testing is improving, there is still a lack of highly trained health care workers.

“You can’t create a doctor, a nurse or midwife in three or four months to respond to the current needs,” he said. “All the resources in the world can’t do that.”

Read the original article on Devex