Coronavirus exposes dangerous gaps in US health care

Boston Globe

Vanessa Kerry

May 21, 2020

Every shift where I don my surgical mask and face shield to treat patient after patient — and see their underlying conditions, and try to discern how to navigate this new and fully altered world — I can’t shake the stark reality that the nation could be doing better.

COVID-19 has killed hundreds of thousands of people worldwide, but beyond lives lost, it has exposed massive and long-concealed gaps in health systems around the world — especially in the United States.

These gaps, and how countries value public health and the systems delivering it, must be addressed now, because another pandemic is all but a certainty. Doing so is well within the capacity of the United States.

Clinicians have already established that COVID-19 preys on the most vulnerable patients. Data from China, France, the United States, and elsewhere show those with preexisting conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, or pulmonary disease are more likely to die from the coronavirus than healthier people.

These trends are especially troublesome for the United States, since such combinations of illnesses are more prevalent based on a person’s race, economic conditions, and place of residence. The South is the poorest region in the country and has higher percentages of each of these conditions. The challenge is that many living there lack access to high-quality doctors and care, yet nine of 14 states in the South have chosen not to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

Access to the basic health care that Medicaid can provide is important, both for personal and public health. A Gallup poll from 2019 showed a record 25 percent of Americans said they or a family member had put off treatment for a serious medical condition during the prior year because of the cost.

Therefore, a failure to address disparities in pre-existing conditions, and provide health care coverage through Medicaid or another means, may have increased the risk of serious illness or death to those who became infected with the coronavirus if they lived in certain parts of the country, or were members of specific demographic groups.

As a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, I’ve helped provide intensive care to coronavirus patients. COVID-19 has come on like a biblical scourge. The patients I’ve seen have been profoundly sick. Many have spent prolonged periods on ventilators, suffering from multisystem organ failures and other complications.

It has taken doctors all we’ve learned in medical school, years of clinical practice, and all the front-line experience gained the past several months to treat and help these patients recover.

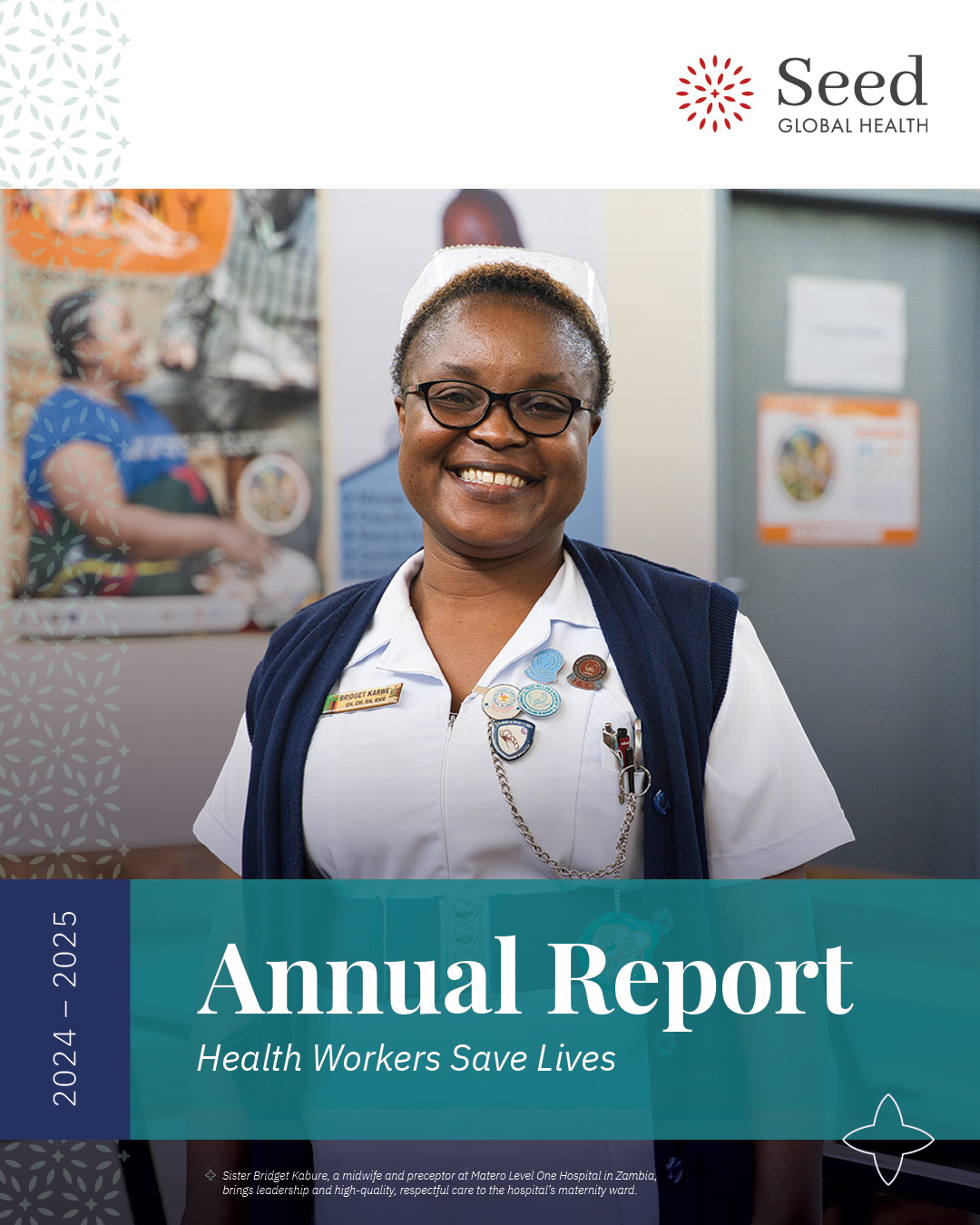

My view is informed by running Seed Global Health, a non-governmental organization that partners with governments to train much-needed health care professionals. The goal is to help them provide essential care and education in countries with limited resources.

Disparities in care, whether at home or abroad, matter for several reasons.

Costs are soaring and health challenges are deepening in the United States as health care systems confront not only the coronavirus but a rise in non-communicable diseases and the continued underutilization of primary and preventive care.

The nation also must address an unjustifiably high number of preventable deaths in areas such as infant and maternal mortality. These rates rival those in lesser-developed parts of the world, especially for women of color in the United States.

Additionally, a pandemic like COVID-19 has prompted comparisons between countries based on how they have responded to the disease from political and public health perspectives. That, in turn, has reinforced — or challenged — geopolitical power, and not always in good ways.

During a recent global COVID-19 vaccine meeting, the United States was notably absent. The Trump administration’s decision to suspend payments to the World Health Organization also delivered a further blow to the global coronavirus response, as well as the concept of multilateralism.

The net effect weakened the position of the United States as a global political and health care leader.

By contrast, other countries have found political success and medical stability by investing in public health, and some have displayed remarkable resilience in the face of COVID-19. For example, Vietnam has endured the coronavirus better than might have been expected, given the relative size of its economy and proximity to the virus’ epicenter in China. In a country of 96 million people, there were only 324 documented coronavirus cases as of May 20. It also had no patient deaths. Vietnam has made a commitment to investing in and achieving universal health coverage, as well as strong primary-care networks. Now, it’s reaping the rewards.

In Rwanda, which 25 years ago was seen as a post-genocide failed state, investments in training of its local health workforce, increases in access to primary care, and the development of a health-financing system has resulted in some of the most precipitous declines in HIV, tuberculosis, and maternal mortality of any country in the last 20 years.

The country of 12 million people had only 308 COVID-19 cases as of May 20 — and none of the African continent’s 2,000 deaths.

The United States, given its sheer ingenuity, economic might, and medical expertise, can surely make the same commitment, and plug the same problematic gaps.

Every work shift where I don my surgical mask and face shield to treat patient after patient — and see their underlying conditions, and try to discern how to navigate this new and fully altered world — I can’t shake the stark reality that the nation could be doing better.

The coronavirus pandemic will end one day, but the vulnerability to the next pandemic won’t, unless the United States decides to prioritize public health and close the gaps in the health care system so it can ensure better health for all.

Dr. Vanessa Kerry is a critical-care physician at Massachusetts General Hospital. She also is founder and chief executive officer of Seed Global Health.

Read the original article from Boston Globe